- Renewables Rising

- Posts

- Policy shifts reshape West Africa's energy future

Policy shifts reshape West Africa's energy future

From the newsletter

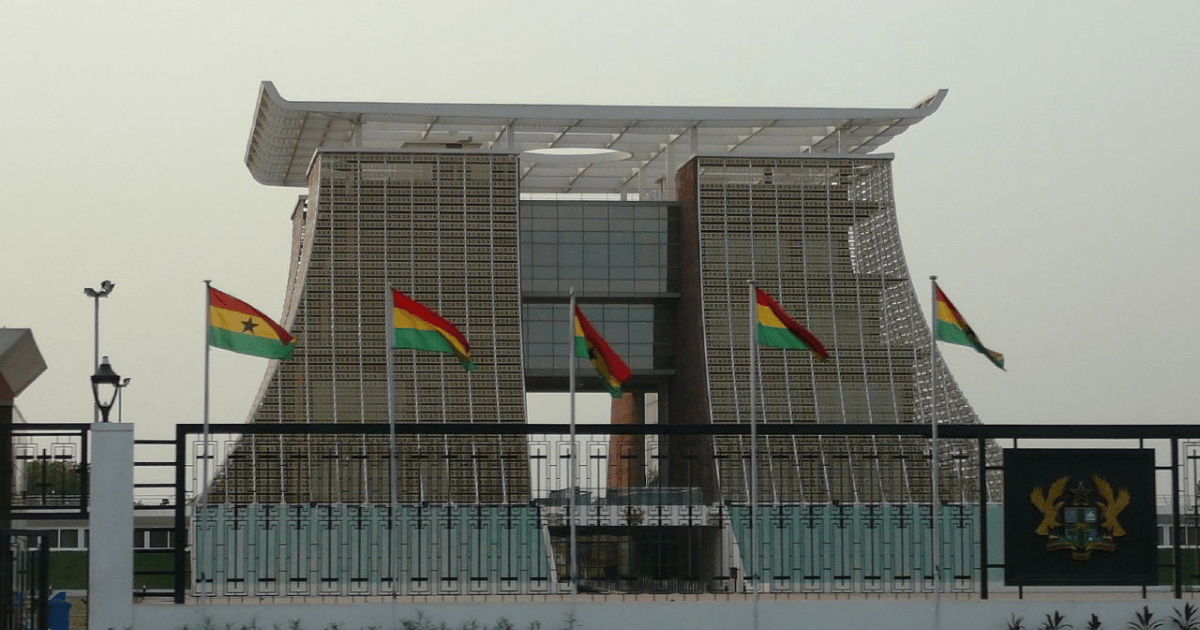

Over the past two months, Africa witnessed two major policy shifts in the energy sector, mainly in West Africa. Nigeria granted regulatory autonomy to 11 states to establish independent electricity markets, while Ghana introduced its 24-hour economy policy, which plans to lower night electricity tariffs and drop import duties on renewable energy systems.

Nigeria’s energy challenges have made it necessary to rebuild the electricity sector to fast-track project development and attract private capital. This follows the path taken by South Africa, Zambia and Kenya.

For Ghana, the 24-hour economy policy marks a big leap, but with the government committing only $300 million out of the $4 billion required for its implementation, its success will depend on private sector buy-in.

More details

Nigeria's move means states can now legislate, generate, transmit, and distribute electricity, particularly in underserved areas. This lays the foundation for a decentralised and more competitive electricity sector. It will enable states to plan better and attract investors by streamlining their policy and regulatory frameworks.

For a country that leads globally in terms of population without electricity, it is hoped that such policy changes will accelerate its progress towards connecting the more than 80 million people by 2030. With less than five years to go, this essentially means connecting at least 16 million people annually to reach the goal. This seems like an insurmountable goal given recent slow progress, with the population growing faster than the electrification rate.

The policy change aligns with the National Energy Compact and other national plans that target the decentralisation of the power sector for faster delivery. Through its rural electricity agency, Nigeria plans to connect more than 17 million people, and plans are underway to have all universities and teaching hospitals generate their own power.

For Ghana, the new policy seeks to overhaul the country’s economic model through incentives, industrial parks, and legal reforms. The initiative will be rolled out in two phases. The first focuses on direct incentives for businesses, ranging from zero import duties on manufacturing inputs to corporate tax rebates, VAT exemptions, discounted night-time electricity tariffs, export rebates, and low-interest credit from the Development Bank Ghana.

The second phase addresses deeper bottlenecks through the creation of large industrial parks in each region, powered by renewable energy. The government projects the creation of 1.7 million jobs within four years, although export, revenue, and employment breakdowns remain vague.

Ghana previously attempted to industrialise the country through the One District, One Factory (1D1F) programme, but the project bore little fruit. Despite a significant amount of money being spent, it only resulted in 169 companies receiving support, and many structural challenges remained unresolved. The 24-hour economy policy risks being nothing more than a political tool to secure elections.

Our take

Ghana's policy risks becoming another political casualty if not effectively backed by legal frameworks. Without this support, it may be more of a political tool for securing elections than a concrete, long-term economic plan, which could be undone with a change in government.

In Nigeria, states with strong leadership, a clear regulatory framework, and a stable economy will likely attract investment and see significant improvements in electrification. In contrast, those with less capacity and fewer resources will struggle, leading to a widening gap in energy access across the country.

For better development, there needs to be greater inter-country and inter-state power sharing. A more connected power sector would provide export opportunities for regions with abundant and low-cost generation capacity. This is similar to a system where power is purchased from the lowest bidder, which is a common approach in competitive energy markets.